Listed out individually, the meanings of these kanji don't really come together to form anything coherent. But then again, the words "lion", "witch", and "wardrobe" hardly sound connected to anyone who's never read Narnia. Much like mentioning Cinderella's glass slipper or Achilles' ever-so-delicate heel, some yoji-jukugo can be used to make an abbreviated reference to the overarching moral of a particular story. 孟母三遷 in particular refers to an old parable about Mencius's upbringing.

Known as the "second Sage", Mencius (or Mengzi as he is traditionally known, but we have Jesuit missionaries to thank for the Latinization) was a famous wayfaring philosopher who practiced and preached the teachings of Confucius. For the sake of brevity, however, we're going to focus less on him and more on his mother, who even now is held up as an exemplary female figure in Chinese culture.

孟母三遷 first appears in the Ancient Traditions of Illustrious Women (古列女傳, Japanese pronunciation: これつじょでん). In this biographical collection of notable Chinese women is an account of Mencius's mother and the choices she made for the sake of her son. The story is well known in Japan as well, and is recounted as follows:

"Mencius's family originally lived near a graveyard. However, young Mencius soon took to playing make-believe funerals, so the family moved near the marketplace. But when they did, Mencius began spending his free time mimicking merchants. So, the family moved again, this time near a school. Only then, surrounded by scholars and academics, did Mencius start behaving with civility and etiquette. Mencius's mother said to herself, 'now this is truly where my child can thrive.' There, the family finally felt at home."

While picturing a young child play-acting funerals and sales pitches sounds like something right out of Calvin & Hobbes (it is, actually), the moral to take away from this story is that environment plays a key role in a child's development, be it social, economic, or even geographical. It is not uncommon in modern-day Tokyo for mothers and fathers to travel sizable distances on their commute into the city. I admit that I initially thought such living situations to be unnecessarily inconvenient; but after reflecting on the lesson to be found in 孟母三遷, I've come to realize that perhaps making that sacrifice so your child can grow up comfortably in the tranquil, forested suburbs isn't so bad after all.

Known as the "second Sage", Mencius (or Mengzi as he is traditionally known, but we have Jesuit missionaries to thank for the Latinization) was a famous wayfaring philosopher who practiced and preached the teachings of Confucius. For the sake of brevity, however, we're going to focus less on him and more on his mother, who even now is held up as an exemplary female figure in Chinese culture.

孟母三遷 first appears in the Ancient Traditions of Illustrious Women (古列女傳, Japanese pronunciation: これつじょでん). In this biographical collection of notable Chinese women is an account of Mencius's mother and the choices she made for the sake of her son. The story is well known in Japan as well, and is recounted as follows:

"Mencius's family originally lived near a graveyard. However, young Mencius soon took to playing make-believe funerals, so the family moved near the marketplace. But when they did, Mencius began spending his free time mimicking merchants. So, the family moved again, this time near a school. Only then, surrounded by scholars and academics, did Mencius start behaving with civility and etiquette. Mencius's mother said to herself, 'now this is truly where my child can thrive.' There, the family finally felt at home."

While picturing a young child play-acting funerals and sales pitches sounds like something right out of Calvin & Hobbes (it is, actually), the moral to take away from this story is that environment plays a key role in a child's development, be it social, economic, or even geographical. It is not uncommon in modern-day Tokyo for mothers and fathers to travel sizable distances on their commute into the city. I admit that I initially thought such living situations to be unnecessarily inconvenient; but after reflecting on the lesson to be found in 孟母三遷, I've come to realize that perhaps making that sacrifice so your child can grow up comfortably in the tranquil, forested suburbs isn't so bad after all.

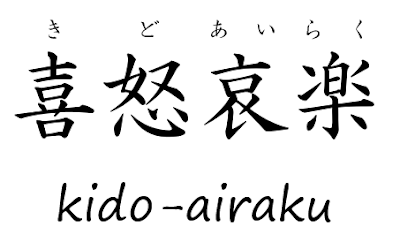

My attempt at a four-word translation of 孟母三遷

Mencius's Mother Knows Best