In our quest to understand more of Japan's yoji-yukugo, we must yet again delve into the massive stockpile of knowledge that is Chinese literary history. The more I research, the more I too am discovering just how many of these idioms come from Chinese literature. This is by no means a bad thing, but for those of you who were hoping for a little more Japanese history in my exposition, I hope you'll understand our somewhat frequent academic journeys to mainland Asia. This week's yoji-jukugo first appeared in the Doctrine of the Mean (中庸, Japanese pronunciation: ちゅうよう), one of the four books of Confucian philosophy. The Doctrine of the Mean was published as a chapter of the Book of Rites (礼記, Japanese pronunciation: らいき), which exists as one of the core texts of the Confucian canon. Due to many revisions, additions, and an historically far-fetched but still culturally influential event known as the burning of the books, it is unclear as to the exact date these texts were published, but it is safe to say that they were well circulated by the end of the BC era.

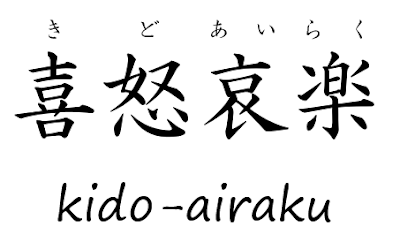

Faithful to the kanji's individual meanings, this yoji-jukugo is defined as "human emotions; joy, anger, pathos, and humor." More specifically, however, the Doctrine of the Mean expresses that these emotions compose morality and dictate human nature. Maintaining a proper rhythm of these emotions is supposedly linked to the ultimate Dao, or "ethical way," of the world.* With this in mind, defining 喜怒哀楽 simply as the four emotions its kanji refer to feels a little lackluster, but I'll try to address that further down the page with my own attempt at a translation.

喜怒哀楽 is among those yoji-jukugo that are still used quite often in modern Japan, one common expression being 喜怒哀楽を顔に現す (きどあいらくをかおにあらわす), meaning "to let one's feelings show on their face." Similar to the old adage "to err is human," Japanese phrases that use this yoji-jukugo seem centered on the idea that showing these emotions, however embarrassing they may be given the situation, are indicative of and intrinsic to human nature. And that's definitely good news for us thespians out there.

*If you care to read the Doctrine of the Mean in English, you can find an expertly translated and diligently annotated version published by Robert Eno here for free.

Faithful to the kanji's individual meanings, this yoji-jukugo is defined as "human emotions; joy, anger, pathos, and humor." More specifically, however, the Doctrine of the Mean expresses that these emotions compose morality and dictate human nature. Maintaining a proper rhythm of these emotions is supposedly linked to the ultimate Dao, or "ethical way," of the world.* With this in mind, defining 喜怒哀楽 simply as the four emotions its kanji refer to feels a little lackluster, but I'll try to address that further down the page with my own attempt at a translation.

喜怒哀楽 is among those yoji-jukugo that are still used quite often in modern Japan, one common expression being 喜怒哀楽を顔に現す (きどあいらくをかおにあらわす), meaning "to let one's feelings show on their face." Similar to the old adage "to err is human," Japanese phrases that use this yoji-jukugo seem centered on the idea that showing these emotions, however embarrassing they may be given the situation, are indicative of and intrinsic to human nature. And that's definitely good news for us thespians out there.

*If you care to read the Doctrine of the Mean in English, you can find an expertly translated and diligently annotated version published by Robert Eno here for free.

My attempt at a four-word translation of 喜怒哀楽

To Feel Is Human